CULPABILITY AND COMPUTER VISION

Machine Vision as a Regime of Truth Complicit in the Murder of Stephon Clark

AUSTIN DAVID WATANABE

BIOGRAPHY:

Austin Watanabe holds a Master of Architecture from University of Minnesota. He is an Architectural Associate at Alchemy Architects. He is also the co-founder of Interesting Tactics, a utopic spatial practice based in Minneapolis, MN. Austin’s work has been published in the Environmental Design-Research Association, the Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, the Man-Environment Research Association, and the International Conference on Robotics and Automation.

This essay was informed by Architecting Anthropoveillance, a graduate course instructed by critic Vahan Misakyan.

![]()

I. COLLATERAL MURDER (VOL. NEXT)

THE MURDER OF STEPHON CLARK

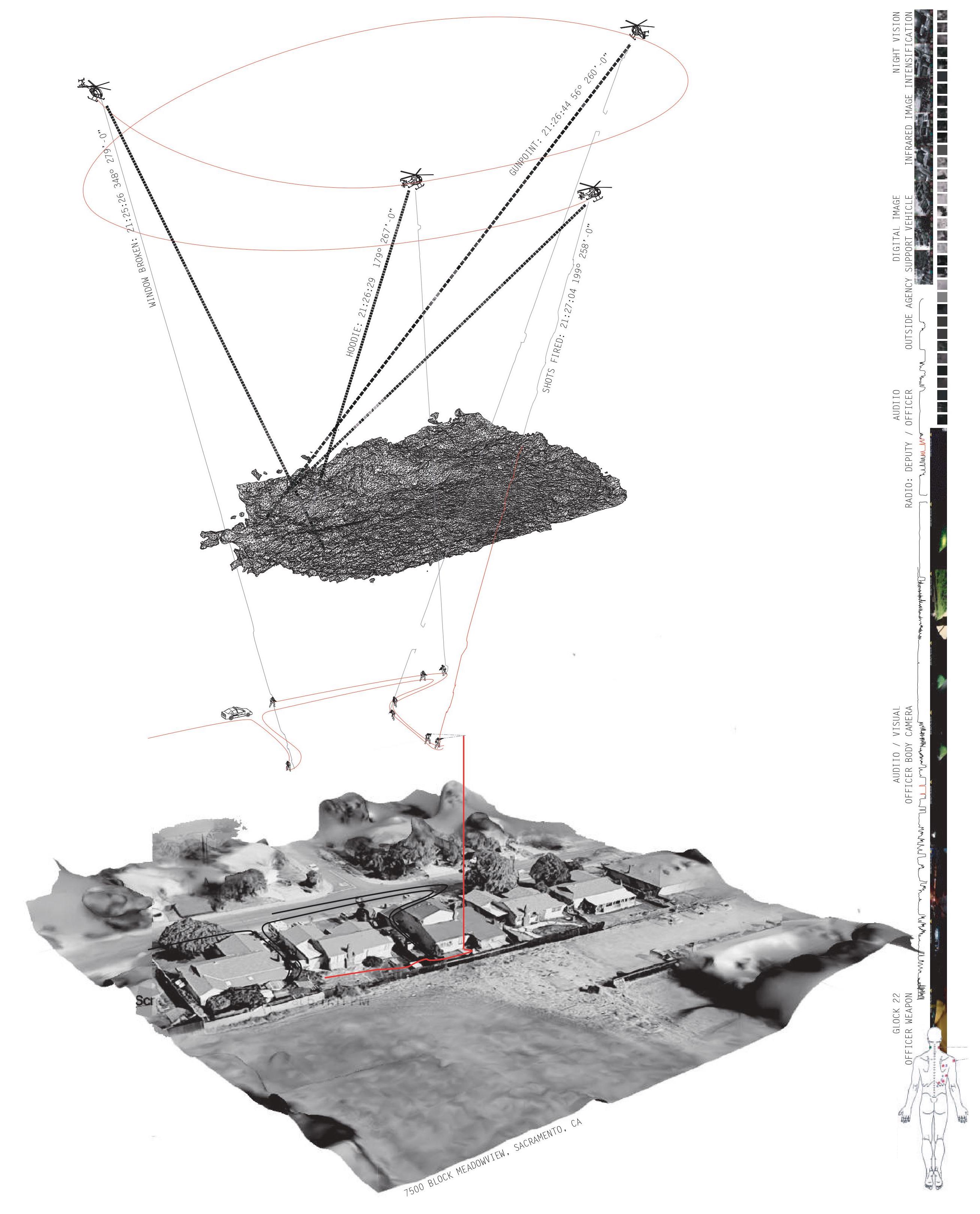

On March 18, 2018, Stephon Clark, was tracked through Meadowview neighborhood in Sacramento, CA to his grandmother’s backyard where he was confronted and shot 8 times by police officers, Terrence Mercadal and Jared Robinet (1). Police had “spotted a man in a backyard and directed police toward him… Deputies told officers that the man had picked up a "toolbar" and [had] broken the window of a home” (1). The false claim that he was armed was made from 279’ above the scene aided by night-vision mistaking Clark’s iPhone for a weapon.

Minutes later, “body camera footage show[ed] that officers intercepted Clark in the backyard of his grandmother's house, and one of them yelled ‘gun!’ as he turned a corner and saw Clark. The officer ducked back momentarily, then looked around the corner again and, shouting ‘gun! gun! gun!’ began rapid fire. His partner then joined in the shooting” (1).

The gravity of Clark’s murder– beyond the loss to his family and community– is the strategic dispersal of responsibility within policing protocol to exculpate any single officer. The authority of machine vision is weaponized through the automated translation of unclear surveillance into lethal intel. Contemporary discourse in architecture provides a means of critically understanding the territory of this event not only through the existing narrative of systemic racism but also the visual and spatial means of exercising control.

![]()

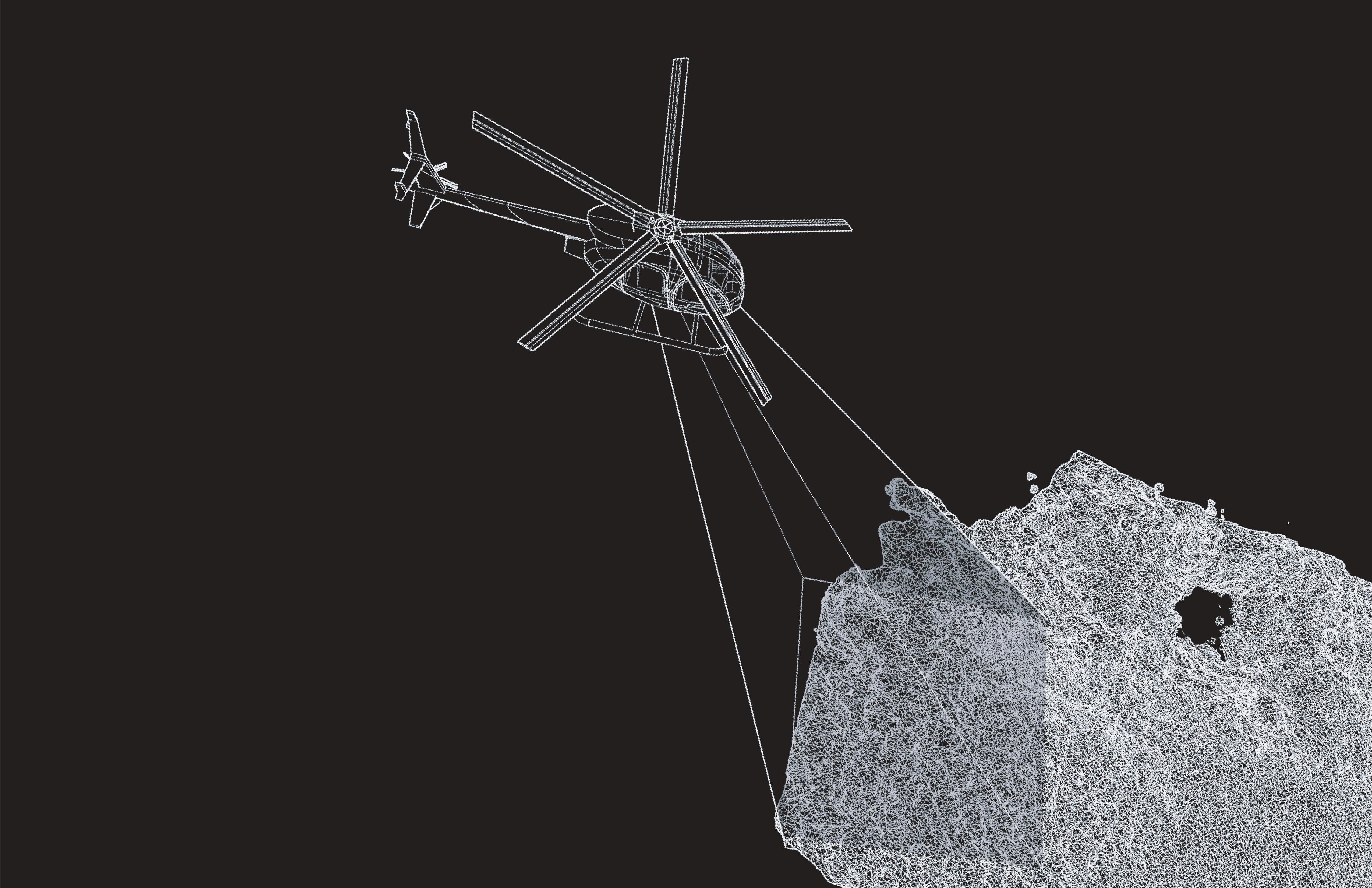

II. MUTING

BODY CAMS DEPLOYED

In the aftermath of the shooting and in a move towards transparency, the Sacramento Police Department released 50 videos and 2 audio clips via YouTube. The quick release of the footage they captured was part of “a larger effort to improve the public's trust” and led to confusion and outrage (2). In the videos the body cameras are muted 16 times. “During their exit, one officer says, ‘Hey, mute.’ Then the audio on both cameras goes silent while the video continues to show authorities responding to the scene” (2). These recordings have “exposed a potential flaw in that effort and opened up a new front in the national debate over body cameras: officers' ability to turn off the microphone on the device” (3).

Sonia Lewis, a cousin of Clark, expressed the significance of the intentional muting: "You're muting something you don't want the public to hear what you're saying, and that means that if you don't want the truth to come out then all of it is a lie." (3)

Cedric Alexander, a former police chief of Rochester, New York, commented on the case: “while the muting didn't appear to break any rules, it looks bad… the problem is the optics of this” (3). This seems like an evidence of their peculiar status within the public space.. PR, Marketing vs democratic oversight

![]()

III. VIDEO HIGH

SURVEILLANCE

In Body Camera Obscura: The Semiotics of Police Video, Caren Myers-Morrison has catalogued the growing archive of video evidence against police brutality. The amassed footage directly opposes the type of rhetoric that Trump’s White House disseminated, namely insisting Clark’s murder to be a “local matter.” (5) She states,

Within the growing body of video evidence capturing the brutality of police, the documentation of Stephon Clark’s murder, unlike Garner, Castile, and Brown, does not emanate from a bystander but is instead produced and disseminated by the police. In this way the video is not a testimonial act of counterveillance, but rather complicit in justifying murder.

John Fiske, the author of Media Matters: Race & Gender in U.S. Politics, proposed a delineator between these two types of footage, video-high and video-low (6). Video-high consists of footage from “top down surveillance” captured by authorities (6). Video-low is an act of counterveillance captured by bystanders in order to undermine the credibility of the authorities. Fiske cites the recording of the Rodney King incident as a seminal instance of these types:

Media Matters was published over 20 years ago, at that time Fiske had written, “the politics of technology itself may be distant, [yet] those of its uses are immediate” (6). In the shooting of Stephon Clark, the technology and politics Fiske describes converge in the weaponization of video-high and the censorship of state-sponsored video-low.

![]()

IV. VIDEO LOW

COUNTERVEILLANCE

Within the dichotomy of video-high and video-low, the regime of truth constructed is inversely proportional to the technology deployed in its production. As Nicholas Mirzoeff noted in his work, An Introduction to Visual Culture: “electronic photography may appear even more ‘objective’ than optical photography” (7). This may seem counterintuitive, especially considering the photoshopped contentsphere of contemporary DeepFakery. However, Fiske breaks down early digital photography:

This phenomena, where eliminating editing capabilities lends legitimacy to the captured image, has become central to discussions around police brutality. For instance, the 2016 police shooting of Philando Castile captured by Diamond Reynolds on Facebook Live eliminated editing capabilities and film stock due to the platform’s settings. This relegated only angle, framing, and focus as relevant variables in the capturing of Castile’s last moments. Despite the judicial outcome acquitting Officer Jeronomio Yanez, the counterveillance method of capture legitimizes the footage in a way that video-high and state-sponsored veillance cannot.

Counterveillance provides claims to truth favoring those with less editing resources– often the same individuals likely to be oppressed under regimes of state surveillance. Gerald Arenberg, the director and founder of the National Association of Chiefs of Police, told a reporter in 1991 “Ever since the Rodney King incident, anyone who has a camcorder is using them.” (6). This need to film tense interactions has been adopted on every side of the political spectrum and the increased prevalence of video-high only increases the potential power of video-low.

The capacity of counterveillance to hold authorities accountable is limited. Myers-Morrison stated, “there is a consensus that outfitting police officers with cameras will be a substantial step toward increased accountability. But we have not come to terms with how indeterminate a visual image can be.” (4) The consensual benefits of bodycams must be questioned in light of Clark’s death when muting and the documentation of the intensity of the scene actually justify murder rather than lead officials and activists to focus on what led to the encounter. Morrison continues “videos will not help us answer the forensic question of why the encounter between the officer and the civilian happened at all, or the normative question of whether it should have” (4). However, when taken as documentation of the scene, these videos do provide a means of modeling and explicating flaws in protocol to hold the system which produced the encounter culpable.

![]() V. FORENSIC ARCHITECTURE

V. FORENSIC ARCHITECTURE

BETWEEN SUBJECT AND OBJECT

Eyal Weizman, founder of Forensic Architecture, described forensics as historically purporting “instances where human testimony is silenced by material readings” (8). His work actively attempts to avoid the prosopopeia of the built environment and instead act as an arbitrator between subjective testimonial and objective material evidence (8).

In his practice, the moving image is dissected to reveal both the capture of subjects/testimony and the ability to project material data/evidence. Weizman directly addresses the “US police brutality against black bodies – where a lot of the evidence that comes out has the perpetrator and the victim captured in a single frame. That is a good piece of footage, and it could become viral because it tells a story” (9).

The composition and antagonism between the staged and captured components of film implies a spatial practice, which can be understood aesthetically. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s analysis of vision corroborates Weizman by describing the inherent movement to viewing:

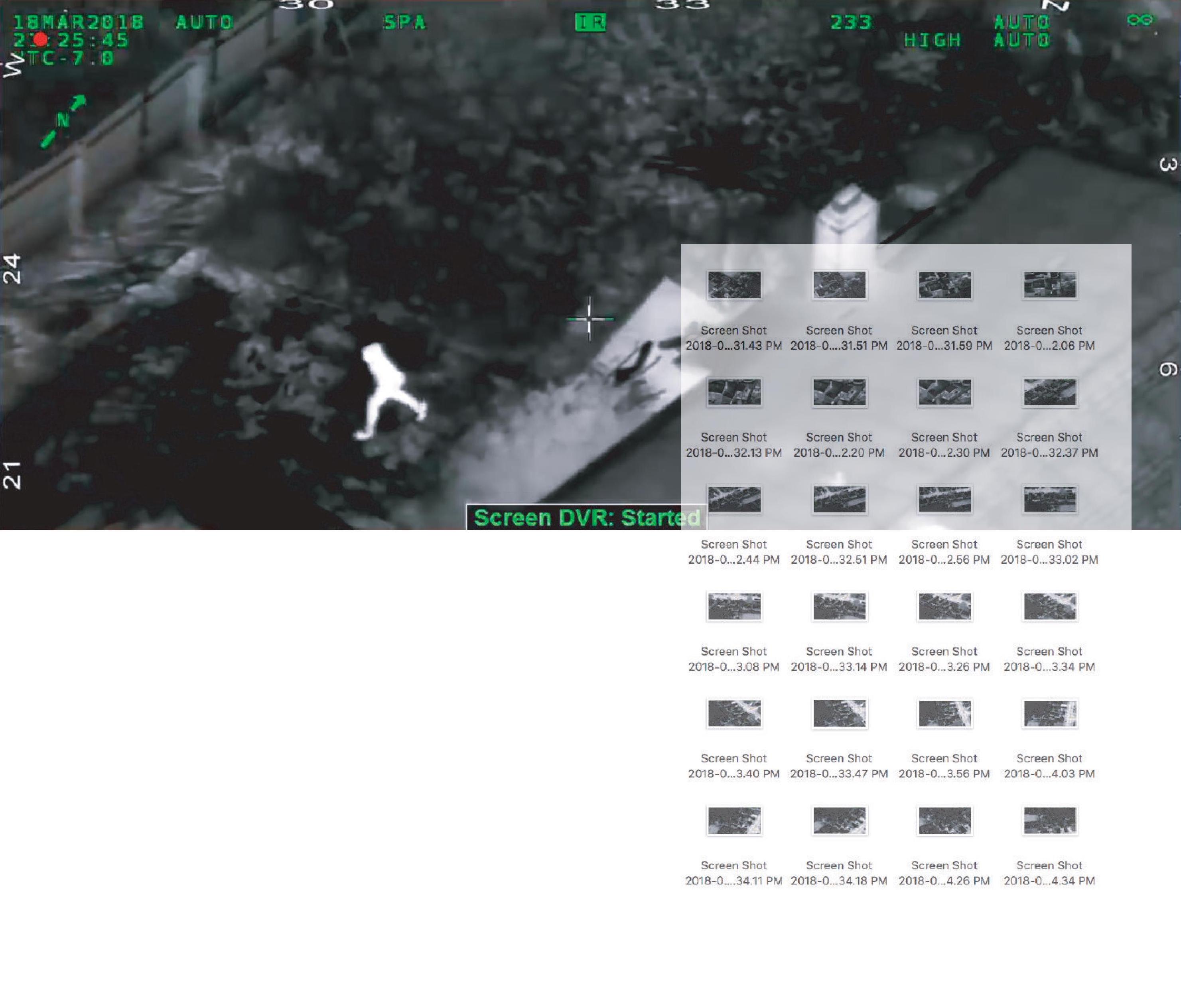

The opposition inherent within vision recalls the panoptic structure of control. In this case, video documentation captures both the subject of the recording and also the location of the camera. A manifestation of this phenomena can be constructed from an SFM (structure from motion) model, a tool used by spatial practitioners which interprets video into three-dimensional models.

Through software like PhotoScan Pro or AutoDesk ReCAP, the uploaded video content is interpolated into a dense point cloud. The point cloud can then be translated to a mesh where the images are compiled into a series of textures on a faceted surface depicting a tracing of Clark through the backyards of Meadowview.

Through this process, the model simultaneously constructs a series of points triangulating the origin of the individual image’s capture. The entire model can then be scaled, lending a measurability to the model. Through this scaling, the helicopter can be accurately pinpointed to 279 feet above the site at the moment when misinformation was assessed and disseminated.

The SFM process appears as follows:

.avi (audio visual interleaved) > point cloud > dense point cloud > mesh > .obj

The process here is a calculable reconstruction of the scene. However the scene’s form does not remotely constitute a replica of Clark’s grandmother’s home. Instead, it is an alien landscape jagged, unclear and imprecise. The quality of this model is significant considering that a similar process was administered by the police and the same jumble of data points was used to extrapolate misinformation that subsequently justified Clark’s death.

The state sponsored process on March 18, 2018:

Night vision: Photons > Electrons> Multiplied Electrons> Photons> NVD image>

Night vision Technician >Radio audio (released in video of Night Vision) > Radio Waves >

Officers > Radio> Body > .40-caliber Sig Sauer P226 and a 9 mm Glock 19 >

“ ‘We’re fixed and dilated here,” a first responder says, an apparent reference to Clark’s pupils showing no signs of life. “He’s gone … total flat,” a responder says. (3)

“Then someone makes the call to document his time of death and asks the time. The answer comes. ‘21:42’ ” (3).

![]()

VI. MACHINE VISION

TRANSLATING PROSTHETIC VISION

In Wigley’s terms, the helicopter becomes a prosthesis of motor power. Equipped with night vision, it becomes a prosthesis of vision. The Sacramento deputies sought to overcome the limits of both darkness and distance. However, these tools and the images they capture are fallible to fabrication, projection, and racism. Neither machines nor the images they produce are benign nor are their consequences. The residue of history and judgement jam the automation of the prosthetic policing assemblage and the biases that corrupt the translation of data to dialogue and ultimately death.

this seems like an important sentence but its hard to follow. You can bring more familiar/mundane terms "biases that corrupt the translation " " dialogue and death" to the beginning of the sentence, and the terms like "residue of history and judgement," "automation of prosthetic policing" to the end, it'll make it more readable.

On March 2, 2019 both officers, Terrence Mercadal and Jared Robinet, were exonerated. In her press release, the Sacramento County District Attorney stated “when we look at the facts and the law, and we follow our ethical responsibilities, the answer... is no– [the officers did not break the law]” (12). The absence of a charge in Stephon Clark’s case is abhorrent but reinforces the presence of a systemic failure in recognizing computer vision as a fallible and compromising component of policing.

Were this case to have ever gone to trial, the jury would have been asked to adopt the shooters’ perspective. Armed with a Glock 22 and misinformation regarding the potential threat of Clark, would the members of a jury fault the officers for their actions? Perhaps a more pressing question is, how much longer will aw enforcement be permitted to supply such limited, ultimately fatal information through the automated lens of apparent objectivity without confronting the protocol that led to the encounter?

As Morrison claims, “the problem with use of force by police is not that officers are setting out to kill black men but rather that they are escalating each step of the situation when they confront black individuals, making a deadly outcome more likely” (4). This “problem” is compounded when impartiality is assumed of semi-automated policing assemblages.

In Civilization and Its Discontents, Freud also makes reference to prosthetics, when “he puts on all his auxiliary organs he is truly magnificent; but those organs have not grown on to him and they still give him much trouble at times" (13). The murder of Stephon Clark cannot be relegated to simply a growing pain in our adoption of a complete control society. Rather, his death ought to be a harbinger of the embedded biases within policing protocol which are heightened rather than avoided through automation.

![]()

This essay was informed by Architecting Anthropoveillance, a graduate course instructed by critic Vahan Misakyan.

I. COLLATERAL MURDER (VOL. NEXT)

THE MURDER OF STEPHON CLARK

On March 18, 2018, Stephon Clark, was tracked through Meadowview neighborhood in Sacramento, CA to his grandmother’s backyard where he was confronted and shot 8 times by police officers, Terrence Mercadal and Jared Robinet (1). Police had “spotted a man in a backyard and directed police toward him… Deputies told officers that the man had picked up a "toolbar" and [had] broken the window of a home” (1). The false claim that he was armed was made from 279’ above the scene aided by night-vision mistaking Clark’s iPhone for a weapon.

Minutes later, “body camera footage show[ed] that officers intercepted Clark in the backyard of his grandmother's house, and one of them yelled ‘gun!’ as he turned a corner and saw Clark. The officer ducked back momentarily, then looked around the corner again and, shouting ‘gun! gun! gun!’ began rapid fire. His partner then joined in the shooting” (1).

The gravity of Clark’s murder– beyond the loss to his family and community– is the strategic dispersal of responsibility within policing protocol to exculpate any single officer. The authority of machine vision is weaponized through the automated translation of unclear surveillance into lethal intel. Contemporary discourse in architecture provides a means of critically understanding the territory of this event not only through the existing narrative of systemic racism but also the visual and spatial means of exercising control.

II. MUTING

BODY CAMS DEPLOYED

In the aftermath of the shooting and in a move towards transparency, the Sacramento Police Department released 50 videos and 2 audio clips via YouTube. The quick release of the footage they captured was part of “a larger effort to improve the public's trust” and led to confusion and outrage (2). In the videos the body cameras are muted 16 times. “During their exit, one officer says, ‘Hey, mute.’ Then the audio on both cameras goes silent while the video continues to show authorities responding to the scene” (2). These recordings have “exposed a potential flaw in that effort and opened up a new front in the national debate over body cameras: officers' ability to turn off the microphone on the device” (3).

Sonia Lewis, a cousin of Clark, expressed the significance of the intentional muting: "You're muting something you don't want the public to hear what you're saying, and that means that if you don't want the truth to come out then all of it is a lie." (3)

Cedric Alexander, a former police chief of Rochester, New York, commented on the case: “while the muting didn't appear to break any rules, it looks bad… the problem is the optics of this” (3). This seems like an evidence of their peculiar status within the public space.. PR, Marketing vs democratic oversight

III. VIDEO HIGH

SURVEILLANCE

In Body Camera Obscura: The Semiotics of Police Video, Caren Myers-Morrison has catalogued the growing archive of video evidence against police brutality. The amassed footage directly opposes the type of rhetoric that Trump’s White House disseminated, namely insisting Clark’s murder to be a “local matter.” (5) She states,

Lethal police violence has always existed, but it has not always commanded sustained public attention. Video has changed that. To talk about police violence these days is to evoke a series of images– Eric Garner sagging in a police chokehold, Philando Castile expiring in the seat next to his girlfriend, Michael Brown's body lying in the street that have turned what used to be discrete local stories into a national issue (4).

Within the growing body of video evidence capturing the brutality of police, the documentation of Stephon Clark’s murder, unlike Garner, Castile, and Brown, does not emanate from a bystander but is instead produced and disseminated by the police. In this way the video is not a testimonial act of counterveillance, but rather complicit in justifying murder.

John Fiske, the author of Media Matters: Race & Gender in U.S. Politics, proposed a delineator between these two types of footage, video-high and video-low (6). Video-high consists of footage from “top down surveillance” captured by authorities (6). Video-low is an act of counterveillance captured by bystanders in order to undermine the credibility of the authorities. Fiske cites the recording of the Rodney King incident as a seminal instance of these types:

In the domain of the low (low capital, low technology, low power) video has an authenticity that results from its user’s lack of resources to intervene in its technology. When capital, technology, and power are high, however, the ability to intervene, technologically and socially, is enhanced. The video-high of Rodney King was a product of capital, technology and social power that lay beyond the reach of the video-low. Because technology requires capital, it is never equally distributed or apolitical. George Holliday [the bystander] owned a camera, but not a computer enhancer, he could produce and replay an electronic image, but could not slow it, reverse it, freeze it, or write upon it, and his videolow appeared so authentic to so many precisely because he could not. The enhanced clarity of the videohigh lost the authenticity of the low but gained the power to tell its own truth in its own domain of the courtroom and the jury room. And the domain was, in this case, the limit of its own victory. (6)

Media Matters was published over 20 years ago, at that time Fiske had written, “the politics of technology itself may be distant, [yet] those of its uses are immediate” (6). In the shooting of Stephon Clark, the technology and politics Fiske describes converge in the weaponization of video-high and the censorship of state-sponsored video-low.

IV. VIDEO LOW

COUNTERVEILLANCE

Within the dichotomy of video-high and video-low, the regime of truth constructed is inversely proportional to the technology deployed in its production. As Nicholas Mirzoeff noted in his work, An Introduction to Visual Culture: “electronic photography may appear even more ‘objective’ than optical photography” (7). This may seem counterintuitive, especially considering the photoshopped contentsphere of contemporary DeepFakery. However, Fiske breaks down early digital photography:

The camera, however, is limited to the semiotic control over encoding the message to two points of human intervention in the process– [A] the choice of angle, framing, focus, or film stock when the photograph is taken, and [B] the darkroom processes as it is developed and printed. In low-tech electronic photography even these choices appear to be reduced, for the darkroom is eliminated. (6)

This phenomena, where eliminating editing capabilities lends legitimacy to the captured image, has become central to discussions around police brutality. For instance, the 2016 police shooting of Philando Castile captured by Diamond Reynolds on Facebook Live eliminated editing capabilities and film stock due to the platform’s settings. This relegated only angle, framing, and focus as relevant variables in the capturing of Castile’s last moments. Despite the judicial outcome acquitting Officer Jeronomio Yanez, the counterveillance method of capture legitimizes the footage in a way that video-high and state-sponsored veillance cannot.

Counterveillance provides claims to truth favoring those with less editing resources– often the same individuals likely to be oppressed under regimes of state surveillance. Gerald Arenberg, the director and founder of the National Association of Chiefs of Police, told a reporter in 1991 “Ever since the Rodney King incident, anyone who has a camcorder is using them.” (6). This need to film tense interactions has been adopted on every side of the political spectrum and the increased prevalence of video-high only increases the potential power of video-low.

The capacity of counterveillance to hold authorities accountable is limited. Myers-Morrison stated, “there is a consensus that outfitting police officers with cameras will be a substantial step toward increased accountability. But we have not come to terms with how indeterminate a visual image can be.” (4) The consensual benefits of bodycams must be questioned in light of Clark’s death when muting and the documentation of the intensity of the scene actually justify murder rather than lead officials and activists to focus on what led to the encounter. Morrison continues “videos will not help us answer the forensic question of why the encounter between the officer and the civilian happened at all, or the normative question of whether it should have” (4). However, when taken as documentation of the scene, these videos do provide a means of modeling and explicating flaws in protocol to hold the system which produced the encounter culpable.

V. FORENSIC ARCHITECTURE

V. FORENSIC ARCHITECTUREBETWEEN SUBJECT AND OBJECT

Eyal Weizman, founder of Forensic Architecture, described forensics as historically purporting “instances where human testimony is silenced by material readings” (8). His work actively attempts to avoid the prosopopeia of the built environment and instead act as an arbitrator between subjective testimonial and objective material evidence (8).

In his practice, the moving image is dissected to reveal both the capture of subjects/testimony and the ability to project material data/evidence. Weizman directly addresses the “US police brutality against black bodies – where a lot of the evidence that comes out has the perpetrator and the victim captured in a single frame. That is a good piece of footage, and it could become viral because it tells a story” (9).

The composition and antagonism between the staged and captured components of film implies a spatial practice, which can be understood aesthetically. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s analysis of vision corroborates Weizman by describing the inherent movement to viewing:

The eye cannot for a moment remain in a particular state determined by the object it looks upon. On the contrary, it is forced to a sort of opposition, which, in contrasting extreme with extreme, intermediate degree with intermediate degree, at the same time combines these opposite impressions, and thus ever tends to be whole, whether the impressions are successive or simultaneous and confined to one (10).

The opposition inherent within vision recalls the panoptic structure of control. In this case, video documentation captures both the subject of the recording and also the location of the camera. A manifestation of this phenomena can be constructed from an SFM (structure from motion) model, a tool used by spatial practitioners which interprets video into three-dimensional models.

Through software like PhotoScan Pro or AutoDesk ReCAP, the uploaded video content is interpolated into a dense point cloud. The point cloud can then be translated to a mesh where the images are compiled into a series of textures on a faceted surface depicting a tracing of Clark through the backyards of Meadowview.

Through this process, the model simultaneously constructs a series of points triangulating the origin of the individual image’s capture. The entire model can then be scaled, lending a measurability to the model. Through this scaling, the helicopter can be accurately pinpointed to 279 feet above the site at the moment when misinformation was assessed and disseminated.

The SFM process appears as follows:

.avi (audio visual interleaved) > point cloud > dense point cloud > mesh > .obj

The process here is a calculable reconstruction of the scene. However the scene’s form does not remotely constitute a replica of Clark’s grandmother’s home. Instead, it is an alien landscape jagged, unclear and imprecise. The quality of this model is significant considering that a similar process was administered by the police and the same jumble of data points was used to extrapolate misinformation that subsequently justified Clark’s death.

The state sponsored process on March 18, 2018:

Night vision: Photons > Electrons> Multiplied Electrons> Photons> NVD image>

Night vision Technician >Radio audio (released in video of Night Vision) > Radio Waves >

Officers > Radio> Body > .40-caliber Sig Sauer P226 and a 9 mm Glock 19 >

“ ‘We’re fixed and dilated here,” a first responder says, an apparent reference to Clark’s pupils showing no signs of life. “He’s gone … total flat,” a responder says. (3)

“Then someone makes the call to document his time of death and asks the time. The answer comes. ‘21:42’ ” (3).

VI. MACHINE VISION

TRANSLATING PROSTHETIC VISION

With every tool man is perfecting his own organs, whether motor or sensory, or is removing the limits to their functioning. Motor power places gigantic forces at his disposal, which, like his muscles, he can employ in any direction; thanks to ships and aircraft neither water nor air can hinder his movements; by means of spectacles he corrects defects in the lens of his own eye; by means of the telescope he sees into the far distance; and by means of the microscope he overcomes the limits of visibility set by the structure of his retina (11) – Mark Wigley Prosthetic Theory

In Wigley’s terms, the helicopter becomes a prosthesis of motor power. Equipped with night vision, it becomes a prosthesis of vision. The Sacramento deputies sought to overcome the limits of both darkness and distance. However, these tools and the images they capture are fallible to fabrication, projection, and racism. Neither machines nor the images they produce are benign nor are their consequences. The residue of history and judgement jam the automation of the prosthetic policing assemblage and the biases that corrupt the translation of data to dialogue and ultimately death.

this seems like an important sentence but its hard to follow. You can bring more familiar/mundane terms "biases that corrupt the translation " " dialogue and death" to the beginning of the sentence, and the terms like "residue of history and judgement," "automation of prosthetic policing" to the end, it'll make it more readable.

On March 2, 2019 both officers, Terrence Mercadal and Jared Robinet, were exonerated. In her press release, the Sacramento County District Attorney stated “when we look at the facts and the law, and we follow our ethical responsibilities, the answer... is no– [the officers did not break the law]” (12). The absence of a charge in Stephon Clark’s case is abhorrent but reinforces the presence of a systemic failure in recognizing computer vision as a fallible and compromising component of policing.

Were this case to have ever gone to trial, the jury would have been asked to adopt the shooters’ perspective. Armed with a Glock 22 and misinformation regarding the potential threat of Clark, would the members of a jury fault the officers for their actions? Perhaps a more pressing question is, how much longer will aw enforcement be permitted to supply such limited, ultimately fatal information through the automated lens of apparent objectivity without confronting the protocol that led to the encounter?

As Morrison claims, “the problem with use of force by police is not that officers are setting out to kill black men but rather that they are escalating each step of the situation when they confront black individuals, making a deadly outcome more likely” (4). This “problem” is compounded when impartiality is assumed of semi-automated policing assemblages.

In Civilization and Its Discontents, Freud also makes reference to prosthetics, when “he puts on all his auxiliary organs he is truly magnificent; but those organs have not grown on to him and they still give him much trouble at times" (13). The murder of Stephon Clark cannot be relegated to simply a growing pain in our adoption of a complete control society. Rather, his death ought to be a harbinger of the embedded biases within policing protocol which are heightened rather than avoided through automation.

ENDNOTES

- St. John, Paige and Serna, Joseph. "Stephon Clark Was Shot Six Times In The Back By Police, Independent Autopsy Finds." LAtimes.Com. N. P., 2018. Web. 23 Apr. 2018.

- Horton, Alex. "After Stephon Clark’s Death, New Videos Show Police Muted Body Cameras At Least 16 Times." Washington Post. N. P., 2018. Web. 8 May 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/

- Schuppe, John. "Police Shot Stephon Clark then Their Body Cams Went Mute.." NBC News. N. P., 2018. Web. 23 Apr. 2018.

- Myers-Morrison, Caren. (2016). Body Camera Obscura: The Semiotics Of Police Video. Ssrn Electronic Journal.

- Reilly, Katie. “Trump White House Calls Fatal Police Shooting of Stephon Clark a 'Local Matter' Time Magazine Online. "Http://Time.Com." Time. N. p., 2019. Web. 3 Mar. 2019.

- Fiske, John and Hancock, Black Hawk. (2016). Media Matters: Race & Gender In U.S. Politics. 1st Ed. Minnesota Press.

- Mirzoeff, Nicholas. (2013). The Visual Culture Reader. London: Routledge.

- Weizman, Eyal. “Forensic Investigations Of Designed Destructions In Gaza - The Funambulist Magazine.” The Funambulist Magazine. N. P., 2018. Web. 8 May 2018.

- Weizman, E. Bernard, Policinski. International Review Of The Red Cross (2016), 98 (1), P.21–35. War In Cities.

- Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von. "Theory Of Colours." Google Books. N. P., 2018. Web. 8 May 2018.

- Wigley, Mark. Prosthetic Theory: The Disciplining Of Architecture. Assemblage No. 15 (Aug., 1991), P.6-29

- Ray Sanchez and Steve Almasy, CNN. "No Charges For Sacramento Officers Who Fatally Shot Stephon Clark ." CNN. N. p., 2019. Web. 3 Mar. 2019.

- Freud, Sigmund. (1933). Civilization And Its Discontents. Journal Of Educational Sociology, P.568.